Talking shop with colleagues after a recent show, the topic of writing arose again. We discussed who we come up with premises, how we develop our ideas, how we find punchlines and what we do about writer’s block.

Writer’s block. Is it a real thing? I’m not sure, but it always looms and strikes fear in our hearts.

I suspect the fear and other negative symptoms that hitting a speed bump or road block induces come from a couple of different ideas, and I feel that these ideas are objectively wrong.

The first of these ideas is that jokes are precious. In my book I downplay this attitude, stating that the belief jokes are rare and almost impossible to create comes from an unhelpful scarcity mindset. The belief that jokes are rare and impossible to replace is why comics sometimes take the kind of jokes to the stage that aren’t very good, or can work against them and even get them cancelled in some situations.

You have to believe that your brand/act/reputation/identity/persona is more valuable than any single joke, otherwise you’ll end up undermining your own foundations or delivering sub-standard sets. The scarcity mindset also cripples your ability to come up with jokes, so it’s a vicious circle. Dropping it makes jokes come easier, which is a virtuous circle.

The other idea is that jokes necessarily come from discipline and effort. We all acknowledge it, even though we know it’s not the truth most of the time – not for matters of creativity, anyway. It’s part of a larger misconception we all share (something else I discuss in that book I keep going on about) which is the belief that comedy is some kind of meritocracy.

Questioning meritocracy is an extremely counter-intuitive thing to do (but if you’re serious about being a comedian, you definitely need to learn how to do counter-intuitive). First, it seems to be common sense of the most obvious kind. Second, we want to believe in it. It’s an idea we need in order to navigate this world with any degree of success, and also for that sense of fairness and justice we require in order to keep going with it all.

But look around at this world. You don’t need to red-pill yourself too hard before you can see that poverty isn’t guaranteed by immorality (not the victim’s, anyway) and that hard work and good behaviour aren’t any guarantee of wealth. Some of the hardest working people on the planet are poor, and some of the most immoral are among the wealthiest.

Like Free Will and other ideas that fly in the face of abundant evidence, we have to act as though Meritocracy exists even if it’s objectively deniable. We have to act, at least in most areas of our lives, as though hard work and effort are the best and most predictable path to desirable outcomes.

We have to do this, even while accepting that there’s no meritocracy. Do the best, most talented and original comedians make an exclusive club of the world’s most successful? I’d say not. Are the most successful comedians in the world the hardest working? Doubtful. Especially right now when the biggest comics in the world aren’t even bothering with humour, choosing to spend their time with shit-talk podcasts and locking the boots of vile politicians. The biggest names don’t appear to be putting much effort into their comedy at all.

Instinctively we understand that when it comes to getting breaks in comedy, our perceptions of merit and fairness talk more to the way we feel things should be than the way they actually are. But we also know, deep down, that the principle also applies to writing jokes.

Which brings me back to our discussion the other night. It was observed and agreed by everyone there that while we generally feel we ought to work on writing, some of the best material comes to us effortlessly. We’re often surprised by the sudden flash of inspiration when a great joke comes to us, unexpected and unasked for. It makes all the time and effort we put into the rest of our work feel uncompensated and unfair.

It’s true that an absolutely brilliant legendary bit like Gary Gulman’s “How the states got their abbreviations” (and if you’re not familiar with it, check it out immediately. You’ll never see a better example of a well crafted efficient and effective 6 minute routine with the most possible jokes and maximum likeability). Gulman spent years developing this absolute masterclass, and you can tell it’s packed with little gems he’s collected and refined for a long time.

But for every laborious process, there’s the joke that just appears from nowhere. Sometimes it’s a 3am epiphany, sometimes it’s a perverse thought while waiting for the bus, and sometimes it can be suddenly noticing the incredible weirdness of something mundane we’ve always taken for granted before. Sometimes the best ones come to us immediately and effortlessly.

You don’t have to see many music mini-documentaries on YouTube to hear a story about a throwaway idea that nobody worked hard for and nobody took seriously becoming the act’s biggest ever smash hit. At this point, it’s a trope. Truthfully, some of the best ideas come without any strain or commitment.

My friends described the agony of doing what we’re all advised to do by our tribal elders – dedicated and disciplined time spent actively trying to work hard at writing a joke from beginning to end – coming up with the idea, refining and developing it and polishing it until it becomes a finished product. We’re told to set aside blocks of time and approach it like work, and to do that work in a linear way to ensure we finish what we start.

I get it. I don’t follow it, but I do get it. Hard work and discipline don’t guarantee results but they’re a more reliable strategy than simply hoping and praying for divine inspiration to strike. I’m not saying I don’t set aside time to actively craft material, but possibly I do it differently.

I never set out to work a joke from end to end. I can’t see how it would work for me, and I’m certain that there will be a point somewhere in the joke development timeline where I’ll hit a mental speed bump or road block. At this point, I don’t see much profit in hammering away at it until I magically make it through.

Nope, I “put a pin in it” and move on to something else. Something else that I can make some progress with right now.

People don’t love leaving their work unfinished. They worry they won’t come back to it. They worry about losing momentum. They think when they return to the problem they’ll have lost any momentum they had. They suspect if they come back to it, the context will be missing and they’ll struggle to even understand what they were thinking in the first place. They worry that it’s a lazy act of resignation that they’re not even being honest with themselves about.

These are all legitimate concerns. I’ve had them myself. But let me tell you about the Zeigarnik Effect.

Basically, it’s the idea that unfinished or interrupted tasks stay in your memory. In fact, the theory claims that unfinished business stay in your memory better than finished ones. A bunch of different experiments have been conducted to prove it. Apparently the tension of unfinished business keeps it alive for us better than something completed, which our minds tend to archive.

The idea suggests that our mental algorithm keeps running a process in the background while we’re doing other things. It suggests that when we come back to it it’s not only more present in our mind, but we might actually have made some subconscious progress with it in the downtime. This is a thing. It really is. Businesses use this principle when they design software, businesses build it into their practice and educators keep in in mind for students.

Of course, I might be rationalizing because my approach to writing and creativity is largely designed by my laziness. But I personally know that I don’t get much done in a focused beginning-to-end writing session and I’m sure I wouldn’t get anything finished that way. If it’s not working, it’s not working. It always tends to work better later when I come back to it with fresh eyes. And yes, I’m certain that my subconscious has been quietly problem-solving it in the background.

Easy “divinely inspired” ideas are often just as effective as the ones we created with brute force and persistence. Given the choice, I’ll go for the easy ones every single time.

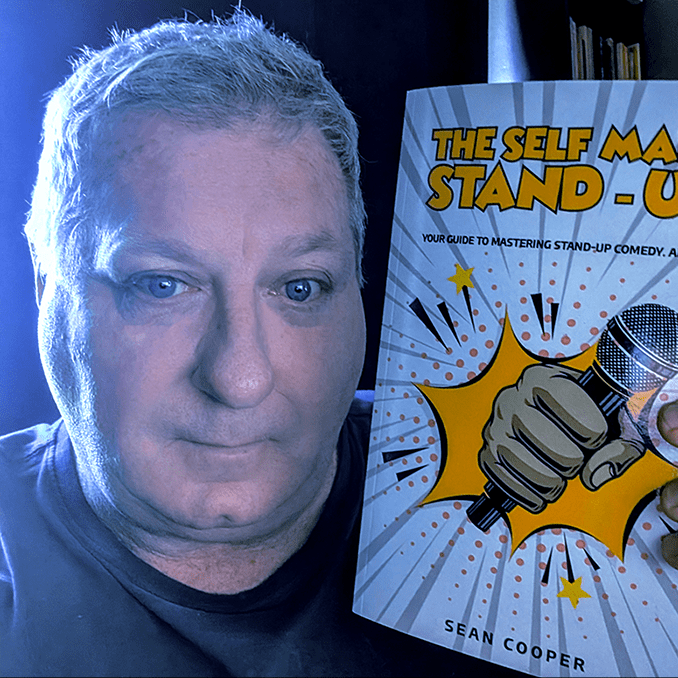

The Self Made Stand Up is available as a paperback or e-book from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Books.By and lots of other places.

More than a how-to book, The Self-Made Stand-Up is an essential resource for developing yourself as an effective comedian. If you’re a comedian, or looking to become one, The Self-Made Stand-Up is the emotional support animal you need.

[…] I’ve implied before that I don’t believe in immediately rushing the seed of an idea to the comedy stage. I’ve got a folder filled with funny ideas that aren’t really jokes yet. It’s a full folder, but I’m adding to it constantly. I’m not troubled by the fact that ideas go into it faster than they come out. Some of them have been in there for years. They might never graduate from this folder and that’s OK. […]

LikeLike