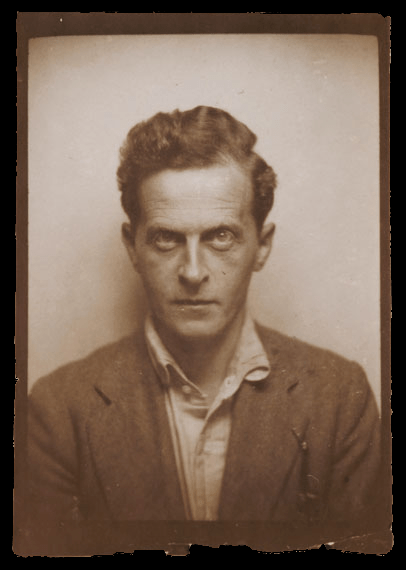

Many of history’s philosophers have something to teach comedians about the nature of what we do. Ludwig Wittgenstein is definitely one of the greatest philosophers the world has known; I will fight anyone who disputes it. He was a philosophical prodigy who wrote the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, before he turned 30 and came up with concepts that dominated 20th century philosophy.

Wittgenstein wasn’t known for his humour though. He had something of a dark disposition. Although his family was one of the richest in Europe, three of his four brothers committed suicide. He also tried himself, but his aim was suicide by enemy soldier. He signed up for World War One and tried his hardest to get himself killed. Instead, he ended up with one of the biggest collections of medals for exceptional bravery ever earned by a soldier.

But what does any of this have to do with stand-up comedy? I’m glad you asked. First, consider this Wittgenstein quote:

“A serious and good philosophical work could be written consisting entirely of jokes”

Yeah, that’s a real thing that he said.

It makes some sense if you read his work. His magnum opus, the Tractatus, can be downloaded here for free if you want to. It’s a trippy read, written a bit like a 1970s prog-rock concept album with track numbers and puzzles, and it loops around on itself so you could theoretically play it on repeat.

But also it’s notably written in the format of formulas, like algebra or mathematical logic. Here’s an example:

2.061 Atomic facts are independent of one another.

2.062 From the existence or non-existence of an atomic fact we cannot infer the existence or non-existence of another.

2.063 The total reality is the world.

2.1 We make to ourselves pictures of facts.

2.11 The picture presents the facts in logical space, the existence and non-existence of atomic facts.

2.12 The picture is a model of reality.

2.13 To the objects correspond in the picture the elements of the picture.

2.131 The elements of the picture stand, in the picture, for the objects.

2.14 The picture consists in the fact that its elements are combined with one another in a definite way.

2.141 The picture is a fact.

Ok, I’m aware that this is a single piece of the puzzle, taken out of context.I’m just trying to show you how he writes and does his logic. That said, we will come back to the point he makes in 2.131 shortly.

It might not be apparent to comedy fans or newcomers to joke writing, but the real language of jokes is algebra. Every joke is a structure that can be expressed as an algebraic formula.

“But what about Puns?” I hear you ask. Well, first let me restate as I’ve told you before that Puns suck and you shouldn’t rely on them too much. But also, let me explain how puns work. There’s two basic styles of pun:

- Some words sound the same even though they mean different things

- Some words are the same even though they mean different things

Tell me you can’t express that as a formula. I dare you. My problem with Puns is that they’re such an easy and obvious formula that you rarely get much more than an “I see what you did there” for using them.

That said, the classic Misdirect isn’t much more complex as far as algebraic formulas go. The classic Counterpoint structure is really just a categorical syllogism, much like the arguments Socrates used to make.

Jokes are math. Specifically, algebra. Just like logic uses. Now that you see it, and see how he constructed the Tractatus, his quote about building a philosophical work from jokes makes a lot more sense, right?

As I said, audiences and newcomers to joke writing don’t immediately see the algebra behind the joke. This is something I see most when people complain about a joke’s supposedly offensive content.

Someone might take umbrage at the content of a joke – a gender, for example – and wonder why their outrage isn’t shared by other comedians. The difference is that the comedians ignore the content and focus on the form of the joke.

Comedians admire the elegant structure of the formula. Comedians know that the gender thing is just a placeholder for x. For this joke structure, x could just as easily been bananas or Lego bricks.

Comedians don’t share your outrage when you hear a joke with content that challenges your sensibilities because to us it’s about the pure structural form. It’s not about the content. You don’t think we’re really obsessed with the motives of chickens crossing public streets, do you?

Now, as promised, I’m referring to part of the quoted text above: 2.131. “The elements of the picture stand, in the picture, for the objects.”

Wittgenstein told us, and this turned into Semiotics and Logical Posivitism and Post Structuralism over the next century, that words are not things. Not only are words not things, they stand in place of things.

Sometimes the word is there because the thing it refers to isn’t and can’t be. I can say something like “Isn’t this a ridiculous cow? I mean, the cow is sexy and menacing, but it’s also kind of hard to take seriously while it’s wearing that hat.”

That’s a weird thing to say, but it’s even weirder that I can say it even though there’s no cow there, and no hat either. We use words as though they hyperlink directly to stuff, but it’s just not the case. We can use words that don’t refer at all, and we can still treat them as though they do.

Sometimes as comedians we have to reassure or correct someone who reacts badly to one of our jokes that it’s victim (and it’s been argues that every joke has a victim) doesn’t exist. Our interlocutors are getting offended on behalf of someone who isn’t real,

Another of Wittgenstein’s ideas about language is that the references and hyperlinks we make to things aren’t as standard or shared as we think they are. He proposed a thought experiment about The Beetle in the Box. It goes a little like this…

A teacher gives every student a box. They can’t show anyone else what’s in their box. He asks them all what’s in their box and everyone says “A beetle. I have a beetle in my box!”

Except maybe they don’t? Maybe they have a beetle. Maybe they have nothing, but for them “beetle” means nothing. They might even have a vial or eye drops, but in their culture, they describe that with the word “beetle.”

We all use the same words but maybe we’re referring to completely different things. How could we possibly know since we only have the commonality or words and language to refer?

In the 1990s I was making plans to marry someone I’d been seeing. We were both going to have a wedding, get married and share a marriage. You’d think we were both on the same page, right? Except when we finally got around to digging a little deeper, we both had very different ideas of what a marriage was. We were using the same language and words, but we were talking about very different things. At the time, marriage was the beetle in my box.

Even when we mean the same thing, it’s not the same thing because there is no thing because words stand in place of things. Like, I tell you about a tree. I describe the tree at length, but there is 0% chance that the tree you picture in your head is the same as the tree in mine.

This is the mutual incommensurability of language, and a gentle reminder that we are all alone. We share a language but all we’re really sharing is the words, not the things. You can never really comprehend my thoughts or experiences and I can never properly comprehend yours.

We never have any insight into each other, not really. The best we can do is use language, hope that we all have roughly the same meaning for “beetle,” and that near enough will be good enough… because it’s impossible to actually look into each other’s boxes.

That’s depressing as a human, but it’s ok for comedians. Remember, we’re interested in the structure of the joke, not it’s content. If I tell you about the grumpy skeleton, it doesn’t really matter if your grumpy skeleton doesn’t resemble mine. It’s just a placeholder for x in my algebraic joke formula.

Smart comics will play to this, and it makes sense for smart Word Economy. Comprehensively describing my grumpy skeleton will weaken my joke. It’ll suck all the momentum out of it, and you won’t laugh.

It’s far more effective to toss you the minimum number of ingredients that you need to construct your own grumpy skeleton. How similar your grumpy skeleton is to mine adds nothing to the desired outcome, but word economy and punchy delivery does. Do the Hemingway thing – describe the tip of the iceberg and let them fabricate the rest themselves. People generally prefer their own icebergs anyway.

Wittgenstein invented the phrase “language games” and it evolved into a whole branch of philosophical inquiry. you might not be interested in philosophy but if you’re a comedian you’ll be very interested in language games. You definitely want to do some thinking about this stuff.

I could talk about Wittgenstein all day. I’m a fan. But I just wanted to leave you with this… He said his mission as a philosopher was to “Der Fliege den Ausweg aus dem Fliegenglas zeigen” or, to show the fly the way out of the bottle.

He saw that language, something we take for granted as one of the important structures in our society, is messy and confusing and frequently obscures reality and meaning. Everyone aims to wake up from The Matrix, and to find reality and meaning. In many ways, this mission statement is something that comedians also aim for.

[…] release in the new year. If you’re new, and a lot of you have tuned in after my post about Ludwig Wittgenstein and what comedians can learn from his philosophy, welcome and thanks for coming along for the […]

LikeLike