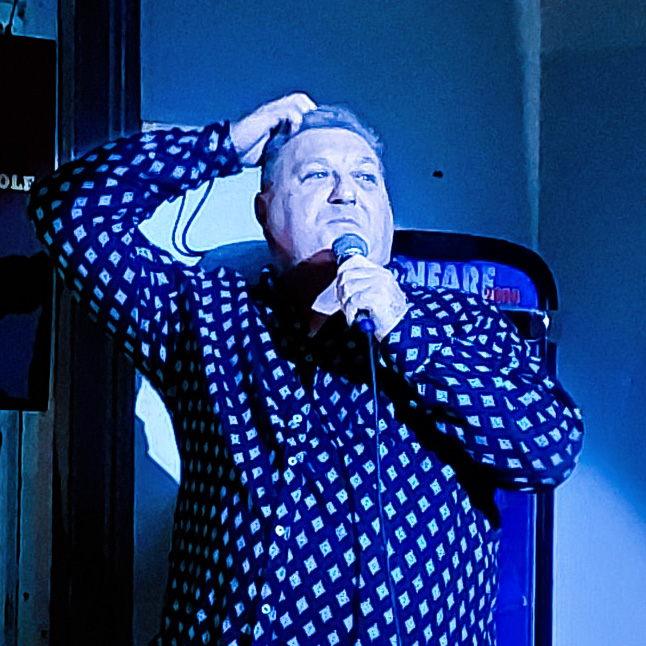

August 19 is my comedy birthday, the anniversary of the first time I nervously stepped up on stage and took the mic with an intent to make people smile and laugh. In 2025 that means I’ve hit the 6 year milestone as a comedian.

Interestingly the most recent gig I did was at the Cen Ten where I did my first set. The venue ceased hosting comedy in 2021 and we’ve all missed it a lot. Now it’s back in action, it’s been an extremely enjoyable and comfortable place to perform… but no wonder I’ve been feeling nostalgic lately.

Anyway, as I often do around birthdays, I’ve done a little mental stock take and assessment of how far I’ve come and what I’ve learned. I’m pleased with the progress and am evolving into being the comic I always hoped I would be. Not only that, but I wrote a book on the craft of it, which I’m proud of. Even better, there are opportunities I can now consider that I previously knew I wasn’t ready or sufficiently skilled for. So I’m feeling pretty good about all of that.

But what’s on my mind right now are some of the things I’ve learned so far on this crazy journey, and this post is to capture six of those things.

- Small talk is annoying.

Comedy teaches us about the importance of efficient and powerful language. It’s not just about coming up with a wacky idea. It’s about delivering that idea as effectively as possible, and that means cutting everything redundant from our speech.

Word Economy becomes our holy grail as we endeavor to increase our impact by phrasing our ideas with as few words as possible. We ruthlessly cut out everything extraneous and ineffective. We’ll drop details that aren’t critical and swap out weaker words for more powerful ones.

We’ll constantly be A/B testing our phrases to ensure we’re maximizing the value of the words we do use. We develop a toolkit of techniques to make our language more persuasive and effective, and filter all of our ideas through that lens before articulating them.

This can make us not very good at small talk. After a few years of parsing our ideas like this, we can get impatient with the meandering waffle and verbal detours that most people’s conversations are constructed with. We’re constantly deciphering ideas and thinking about better ways to deliver them, even when it’s you who’s doing the speaking.

Most people expand their language to fill time, and that’s fine, but we’re not trying to consume time. We’re regularly practicing how to get the most out of the time we have. That can makes us impatient and short with you, especially in our fourth year or so. We start dreading those exchanges where people just want to fill time with conversational pleasantry, we stop being good at that simple social practice. Sorry about that. - Bullshit is bullshit.

I know that most people view stand up comedy as a practice of shit-talking, so you might be surprised to see this point here. Arguably, though, what we do is a process of cutting through bullshit – especially the mundane bullshit that nobody notices or considers problematic.

A good chunk of what we do is finding stuff that’s problematic, perverse, hypocritical, dishonest, ironic or paradoxical in our world, and there’s bonus points if it’s something that slips under the radar because it’s normalized and taken for granted. Nobody is particularly astounded when we point out the obvious.

We develop an approach to developing material that’s centered around a process of interrogating stuff, looking at it from all angles, pulling things apart, putting them in different contexts, all to try and find where the bullshit is in the stuff we see and hear around us.

We’re always doing it because we’re always seeking and developing ideas. We do it systematically and after a couple of years we do it automatically. While we navigate the world around us, we’re constantly running a subconscious search-and-destroy bullshit algorithm in our heads.

Doing this constantly demolishes our tolerance for bullshit. Once upon a time I turned a blind eye to bullshit, or was blinder to it. I viewed bullshit as the cost of doing business in the modern world, and felt obligated to abide it. I also accepted a lot of bullshit because I knew deep down inside that I was putting out a quantum of my own bullshit into the world.

My very last relationship prior to starting my stand-up journey was with someone who, despite being beautiful and intelligent, was full of shit. Basically, this person was a narcissist and pathological liar. I mean, pathological. The lies were constant and completely unnecessary, and I don’t think anybody believed any of it. But nobody ever called her out for it – Not without being cut out of her life, anyway.

The inevitable break up was most of the impetus that got me started in stand-up, and I’m glad, because the process has trained me to identify bullshit and call it out. The process radically diminished my tolerance for bullshit, even from myself. I think the mission to find and develop material for comedy has bullshit elimination as it’s most wonderful by-product. - We have to bet on ourselves.

There’s a thing some comics do. It’s called a “Save.” It’s commenting on a failed joke. A comic might say something that gets a negative response, or none at all, and follow it up with something like “Well that didn’t work.” It usually gets a mild laugh. Acknowledging it, maybe trying to say something amusing about it, is a not-so-secret technique we call a “Save” because that’s it’s primary function and does it quite well.

It’s a legit technique, but there are caveats around it’s use. The main one is that you only get one free Save per set. The second one doesn’t get a laugh, and why should it? If it’s supposed to be a joke, you already did did it three minutes ago.

I know some local comics who use this technique freely. One of them uses it several times in a single set. It’s impressive he can go to that comfortably and doesn’t show any nerves or fear. He’s a confident performer but if I were in his shoes I’d probably be more focused on needing it less.

Another of my peers is guaranteed to resort to this every single gig he does, to a point where I’ve wondered at certain times whether this is actually part of his written act. I mean, every single set for literally years. It’s nice that he has a dignified strategy when something doesn’t land, but at this point it’s the joke he’s done more than anything he ever wrote. Surely, after saying “Well, that didn’t work” every night, there would be an inevitable moment when you actually realize that it didn’t work and try to write something that does?

I feel that while a Save is a handy item to keep up your sleeve, it’s not a great idea most of the time. It’s a last resort and a sign of weakness. Audiences hate weakness even more than a joke they didn’t appreciate, and showing it undermines your act in every way.

We need to bet on ourselves. The act of going on stage and taking the mic is a power move, a statement of strength, and we need to go all in, even if the hand we’re holding could be stronger.

We do ourselves a huge disservice by waving a while flag when a single joke doesn’t get what we expected. The better strategy would be to quickly move onto another joke, and then another, without ever conceding that one of them didn’t get an applause break. If we have to acknowledge a response, it’s better to say that joke wasn’t for you than to claim it was a failure.

We shouldn’t be throwing our own material under the bus at the first indication that it wasn’t sufficiently appreciated. We shouldn’t be throwing our creations under the bus and we shouldn’t throw ourselves under the bus. We might not get the response we expected, but we shouldn’t be so quick to betray ourselves and our material. There’s not a single audience that finds us more endearing or worthy of respect when we do.

Every utterance wont always get a massive laugh from everyone and that’s OK. It’s still what we aim for. At the end of the day we should still bet on ourselves. - Not all “jokes” are actually jokes.

A lot of jokes feel a bit mean. We use violent vernacular about humour. We call the effective part of the joke a “punch” and when we do exceptionally well in a room we’ll say that we “killed.” If we’re not doing well, it’s “bombing.” We talk about the need to be mindful, that we should always be “punching up” and never “punching down,” because we all know that “every joke has a victim” and we don’t want our lethal language to hurt the wrong people.

Jokes can be weaponized and it probably shouldn’t be surprising when someone uses a joke as a Trojan Horse to sneak something destructive and uncool past our filters. It’s becoming increasingly common to see a microaggression described as a joke when it’s called out. Jokes come with a punch. Sometimes the point is the joke, but occasionally the point is the punch.

If that sounds like passive-aggressive bullshit, I might be inclined to agree with you. Right now I’m thinking of one of my peers who, when we do the same show, always manages to go on after I do and begins every set with some jabs at me. It used to seem like playful roasting but it’s gotten ridiculous and lately he seems to have forgotten the joke part (not that it was ever great).

I’m pretty much done with pretending people’s bullshit is comedy when it’s clearly not. In comedy you can get away with pretty much anything as long as it’s funny and the payoff exceeds the cost. When the funny exceeds the mean it’s a joke, but when the mean is greater than the funny you’re probably just being a prick.

I don’t care about whatever passive aggressive notions or repressed rage is being expressed by this guy or anyone else, so I haven’t bothered to engage. I don’t need it. I don’t want it, and there’s nothing compelling me to make it part of my universe. The longer this guy focuses on being nasty instead of funny, the more inevitable and complete his irrelevance in the local comedy scene will become. Don’t ever forget that the jokes come first and that you can’t turn stuff into a joke just by saying it on a comedy stage. - Not all opportunities are positive.

In your first year(s) as a comic there’s a pervasive notion that we must do every gig, to embrace every opportunity and to get as much stage time as possible. This is sound thinking, because racking up your hours on stage is absolutely essential to becoming a decent comic with the tools you need to ensure your show is enjoyed by all.

It would be nice if our craft let us learn and develop before going live and showcasing what we’ve go, there’s no way around the immutable fact that we have to do all of our learning and growing in front of a live studio audience. Yeah, that kinda sucks a bit, and it makes us all feel a little regretful about our appearances at the beginning.

The compulsion to say yes to everything comes in part for this reason, but I suspect a lot of it is also because hustle culture has been such a massive trend over the last decade. Thank goodness we’re beyond that these days because hustle culture is bullshit for many reasons.

Take every available opportunity in comedy for a while and you’ll have some bad experiences. I’m talking about bad gigs, bad audiences, times when your style is a bad match for the show, and good old fashioned burn out.

Two years ago I found myself in a hostile exchange with a comic I know, and the tragic aspect is that this comic is one of the ones I really respect and enjoy, and consider a good friend. Over the next week we were self aware enough to realize that we were burned-out. This was a time when new comedy rooms were opening up in our city every single week and both of us were overworked, over-invested in all of it, and just plain tired.

In addition to all everything else, we were all urged to support our expanding scene by participating in all of it. In my humble opinion, the expansion wasn’t as great or positive as everyone was claiming it to be. All of these new venues and shows outmatched the local demand for comedy, and was too big for the relatively small pool of talent we had in my city at the time.

The result was a constant grind of shows, and most of the new rooms weren’t that well set up for comedy. The same handful of comics were at all of them, as we were all too busy to create any new content for all the shows we were doing. Our respective bodies of work were as exhausted as we were, and the gigs weren’t well attended. How could they be? The market here isn’t that massive, and the established live comedy enthusiasts weren’t interested in seeing the same weary comedians deliver the same weary material endlessly in new and unsuitable environments.

The grind was relentless, the performances were lifeless, and the audiences just weren’t there. The whole exercise was unrewarding and felt like the local scene was cannibalizing itself. Little wonder we were touchy and perspective was lost.

So, yeah… burn out is a thing. So is a bad experience. We develop resilience and necessary experience from the gigs that aren’t optimal, but some gigs just aren’t worth it. We forget that a bad gig can end a prospective career, that many aspiring comics quit the whole project if they have an especially unpleasant time.

I’ve had a great run, personally, but I’ve still witnessed plenty of bad experiences. I’ve seen hostile and aggressive crowds. I’ve seen not-fun nights that resulted in people writing hurtful and shitty things in their blogs and social media the next day. I’ve seen comics in tears. I now appreciate that a bad gig doesn’t always make you stronger – it can damage your self esteem, your reputation, your earnings and your brand.

It’s easy for everyone to forget or overlook how high the stakes really are when we’re up there. On the days we feel bulletproof we tell ourselves there’s no consequences for what we do, but it’s not the whole truth. Not even close.

I’ve come to the conclusion that not only am I not obligated to do all the gigs, I owe it to myself and my act to be selective about what I take on. I emphasize in my book that consistency is really important, and that not being clear about who are you are and what you do makes it hard for your fans to get you and your jokes to work.

Sure, in the first three years we’ll do all the gigs, perform for all of the crowds and try to learn all of the skills. But after that we need to pay more attention to shaping our act and our career, to define who we are and what we do. A big part of this is choosing your venues, audiences and peers.

Taking stock of the venues I perform at, I know I do best at the cocktail bars and cafes I perform regularly at. I also do pretty well at some of the bars and other events. I also do OK at the local Open Mics but I don’t enjoy them as much, especially if the tone is hostile anti-woke edge-lord bullshit. Not only do I not enjoy them, but there’s a good chance that some aspects of them (like passive-aggressive “roast” guy) that are just going to piss me off. But mostly, it’s a bad fit and more likely to undermine the brand and style I’m building than contribute to it.

If there’s anything to that idea about having to embrace every opportunity, I’m happy to be on the other side of it. I think you define and curate your act as much by the stuff you don’t do as much as the stuff you do - Being better is always the correct answer

I’ve written before about the comedy philosophy of making yourself Undeniably Funny, but I’ll quickly recap:

Things often won’t seem fair, and that’s because they aren’t.

Nobody promises absolute fairness and justice in Comedy or anywhere else.

You’re going to feel at times like your effort is greater than your rewards.

You’re going to feel like your value is higher than the value of people who get better breaks and opportunities.

You will sometimes feel like your material and act deserve more love than they get.

This is inevitable: The world of comedy is filled with people who experienced this sensation and responded with bitterness and anger.

Getting angry and combative, encouraging these feelings to grow inside you, is an unproductive and harmful response.

The optimal reaction when you feel like this is to acknowledge that there are factors beyond your control, and that you can only contribute to an outcome with the factors that you do have control over.

Your personal effort and value are not the only factors at play, but your personal effort and value are the only factors you can control. So all you can do – all you should do – is increase your personal effort and value.

This means getting better. Work on your act. Work on yourself.

If you do it well enough and get good enough, become Undeniably Funny, it will be awkward and embarrassing for the universe to not bestow opportunities upon you.

It also ensures that if fortune does knock, you are ready and humbly know that you deserve it.

That’s right, folks. The only answer to injustice and misfortune is to work on yourself and get better. This is, in fact, the only answer to anything. The more you think about it, “work on yourself and get better” is the most useful answer you could have to any question about the world of comedy or any other world.

It’s kind of embarrassing to admit that even though I heard variations on this idea before I entered the world of comedy, it sounded banal and never asserted how salient it is before I started in stand-up. You might be lucky enough to learn it elsewhere, or not. But it’s definitely something the Comedy teaches you, and it teaches it powerfully.

The Self Made Stand Up is available as a paperback or e-book from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Books.By and lots of other places.

More than a how-to book, The Self-Made Stand-Up is an essential resource for developing yourself as an effective comedian. If you’re a comedian, or looking to become one, The Self-Made Stand-Up is the emotional support animal you need.

[…] touched on this matter previously but it cannot possibly be the whole picture. Having recently passed another milestone in terms of my comedy experience, I’m reflecting on some aspects in which sustained practice […]

LikeLike