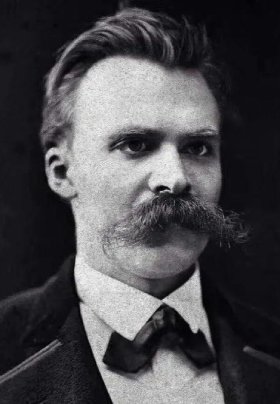

“I would really allow myself to order the ranks of philosophers according to the rank of their laughter” – Friedrich Nietzsche

Nietzsche was a fan of comedy. This should surprise nobody familiar with his work, but I assume nothing because no philosopher in history has been as wildly misunderstood (unless maybe Hegel and Heidegger who are difficult to interpret).

More than any philosopher, Nietzsche embodied the spirit of a comedian. He had so many philosophical ideas that have evolved into cornerstone tenets of stand-up comedy.

I’m not sure he was the first comedic philosopher because Søren Kierkegaard was doing his thing at roughly the same time (I’ll be covering Kierkegaard in a future blog post). Kierkegaard was a comic genius as well as a brilliant philosopher, but Nietzsche really encapsulated the purpose and attitude of comedy.

One of the most basic manifestations is defiance, or asserting one’s own existence in the face of peril. For Nietzsche, laughter as a form of defiance was sign of overcoming. In Thus Spake Zarathustra he said “Not by wrath does one kill but by laughter. Come, let us kill the spirit of gravity!”

Joking, for Nietzsche, was an essential platform for delivering truth. Comics are often described as truth-tellers, people who speak truth to power when the pervasive authority is wrong. He viewed challenging institutions and authorities as one of the most moral acts one can perform, and regarded comedy as the most effective way to do the job. Nietzsche viewed himself as the child in The Emperor’s New Clothes, outside of the self-interest and self-preservation that makes the rest of the crowd falsely flatter and appease the ruler’s empty vanity.

For Nietzsche it was more than just opposing power. It was about revealing hypocrisy and assumptions that are not supported by evidence. He questioned everything, flipping ideas to look at them from a different angle in exactly the same way comedians do when we write jokes.

He’d start with an observation, Jerry Seinfeld style, but then he would attack it from the reverse angle. This, for instance, is how he alienated Christianity – by asking how traditional virtues associated with strength (fight for your rights) got replaced by new virtues that derived from weakness (‘turn the other cheek).

He didn’t just advance and defend a perspective that’s in opposition from the dominant paradigm, which is something every good comedian does, but he also used cheeky humour and polemicism to break taboos. If you’re a comedian and don’t yet appreciate how massive the idea of taboo is in comedy, welcome – I also remember my first day.

Everything comedians do is related to taboos and people’s sacred cows, and this is something we share with the best philosophers. Philosophy is primarily concerned with differentiating between actual reality and socially constructed reality. What that difference is and how we know is, if you’re suffering from writer’s block, a fantastic aid to creating jokes.

Every comedian’s job is to be conscious of taboos, to be aware of all the sacred cows around us, and to challenge them where possible without unduly upsetting people (as Kurt Metzger said on one of his routines, “I don’t want to be killed with a curvy sword!”). The biggest names in comedy whining about “cancel culture” is an acknowledgement of this.

Perhaps the most valid argument for comics is that most people’s sacred cows are individual and personal, and that even the most ardent defender of a sacred cow cares less about other people’s sacred cows than comedians do. Someone can be proactively defensive about a joke that threatens their sacred cow of “unconditional respect for genders” but completely supports trampling all over someone else’s sacred “spiritual beliefs” cow (this particular example of hypocrisy is one that I’ve been guilty of).

For a comic, the frustration is that everyone thinks their cow is sacred and everyone else’s would make great hamburger. Somehow we have to perform the job of interrogating “sacred” status while facing the ire of everyone, because every cow is sacred to someone.

Nietzsche was able to do because he was working from home. If he were on a stage getting critiqued by a crowd in real-time just as his character Zarathustra was, or as a comedian does, he might have had a harder time. Or he might have doubled down and said “Learn to laugh at yourselves as one must laugh!” He actually did write that to his fictional crowd (to whom he referred as “the herd”), and to his real audience.

He recognized what comedians do, which is the attempt to break taboos and invoke Superiority Theory while still being a good person. As he says in Beyond Good and Evil, “Laughter means: being schadenfroh, but with a good conscience.”

And to Nietzsche, the secret to getting away with it is to invoke Benign Violation Theory, violating our sense of how things ought to be and simultaneously showing us that the violation is benign, that the taboo was more of a socially constructed reality than an actual one. If one wanted to be reductive, they could viably characterize all of Nietzsche’s works, from The Birth of Tragedy onwards, as filtering of humanity’s values through a process of benign violation.

Importantly Nietzsche also viewed laughter, comedy and philosophy as a tool with which we can ameliorate and make sense of pain and adversity. He was no stranger to pain and adversity himself. In Beyond Good and Evil he said “Perhaps I know best why it is man alone who laughs: He alone suffers so deeply that he had to invent laughter.”

In my book I’ve written about using the tools of a comedian to process depression, pain, tragedy and adversity. Nietzsche seized upon the idea first. He thought we should interrogate and challenge our assumptions, contextualize violations as benign, and defiantly laugh in the face of difficulty as an assertion of our own existence. He said that the person who masters their life can laugh at “all tragedies, real or imaginary.”

Crucially Nietzsche also argued that our ability to laugh, even at tragedy or the values we define as sacred, as an essential expression of our empathy and humanity. “Whoever wants to learn to love,” he said, “he must learn to laugh.”